The establishment of a fund two years ago to address climate-induced loss and damage was hailed as a major milestone in advancing the global response to the climate crisis by going beyond mitigation and adaptation.

When, in 2022, the global climate dialogue at COP27 paved the way for the creation of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD), and countries pledged to contribute financially, vulnerable nations breathed a sigh of relief.

Loss and damage occurs when mitigation and adaptation efforts fall short, and people begin to suffer irreversible consequences. For example, even after planting trees to mitigate climate change or practising climate-smart agriculture as an adaptation strategy, floods may still wash away crops or drown livestock.

In such catastrophes, people may survive, but lose limbs or suffer permanent injuries. Some losses are economic, others are not, but all underscore the need for the FRLD, with a particular focus on the most vulnerable communities, mostly in the Global South.

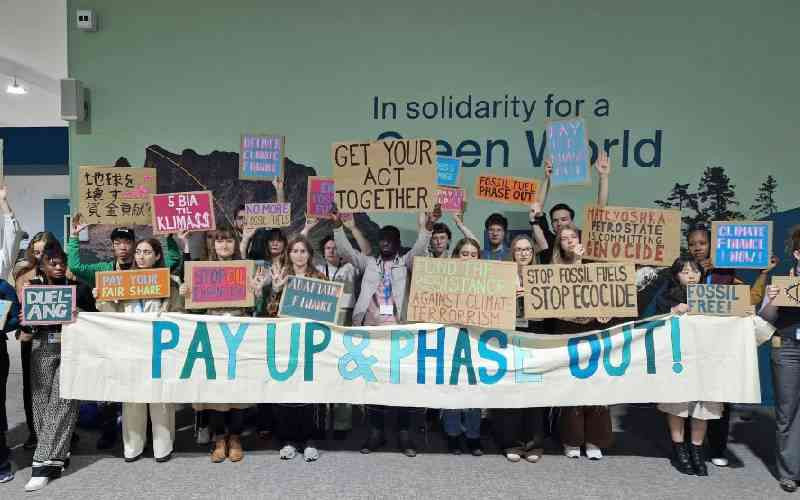

Wealthy nations, some of which bear huge historical responsibility for global emissions, pledged to mobilise at least $789 million. However, only $348 million has so far been raised and disbursed, leaving a considerable shortfall for a fund that was meant to begin with a modest $250 million by 2026.

Estimates suggest that annual funding required for loss and damage may reach $395 billion. This comes on top of an estimated $600 billion needed for mitigation, and a further $187 billion to $359 billion for adaptation. Clearly, the FRLD remains underfunded.

The fund also lacks predictability. There is no certainty as to when pledged contributions will be remitted. Some countries failed to specify timelines for their support. Others have begun contributing, but in what has been described as a “drip-feed”.

This results in devastation and greater human suffering, leading to stagnation, as resources that could have been allocated for development are redirected to managing the irreversible impacts of climate change. I would go so far as to call this economic sabotage, especially considering the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events.

Each flood feels worse than the last. In 2025, for instance, parts of Nairobi experienced flooding of such magnitude that people were literally forced onto rooftops. Cyclones, once rare in Africa, are now a reality. The cost of loss and damage from such catastrophes runs into millions of dollars. Meanwhile, the prolonged drought in the Horn of Africa continues unabated.

Just this week, Unep’s Frontiers 2025 report flagged the rise of a silent, yet potentially deadly, threat of extreme heat that poses particular health risks to older persons. Like floods and droughts, sustained daily temperatures of up to 40°C can be harmful to both humans and livestock, while also curtailing socio-economic activity.

Among older persons, particularly those with chronic illnesses or reduced mobility, such conditions are associated with increased respiratory, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

Unep reports that annual heat-related fatalities among older persons have increased by approximately 85 per cent since the 1990s. The agency is calling for urgent interventions to address these emerging environmental challenges. This, too, requires the mobilisation of climate funds, with priority given to vulnerable populations rather than the private sector.

Solutions exist. They must be both locally led and multilaterally funded. Africa needs both approaches. Supporting the FRLD is not an act of charity; it is a moral and historical responsibility. Only timely action can guarantee global justice and long-term stability.

-The writer is a contributing editor at Mongabay.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter